Programming in Time

When programming, you are working within the concept of time. I am not referring to the standard wall clock time which obviously cannot be avoided. There is a second, more fundamental, form of time.

In an imperative programming language like those within the C family, the language is a state machine. The state is a line number and a map from variable name to value. At each step in the machine, you might read or write to the variable map, and then you move to the next line. If you branch or return, you might move to a completely different line number. At least, this is the basic idea.

The time I am referring to is actually the time-step in the state machine. At each execution, the state machine moves to the next state and the next time-step. So, you can keep track of all of the states your program has gone through and view the history of the program.

If you have used a debugger, you have probably experienced this. When you break, it stops at a particular time-step. When you choose to “go into the function”, that is the next time-step of the machine. Going over a function or continuing executes many time-steps before stopping again.

Consider the simple program below. It checks whether the sum of two numbers is equal to the product.

Int sumEqualsProduct(Int a, Int b) {

Int sum = a + b;

Int prod = a * b;

Bool eq = sum == prod;

return eq;

}

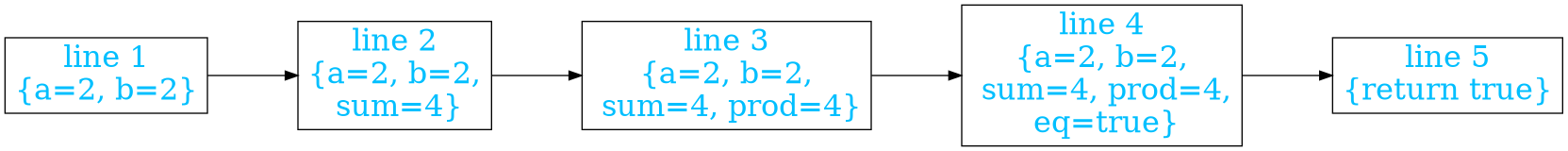

If this program is put into the following diagram, it shows how it behaves imperatively. While this looks reasonable for the most part, note the unnecessary dependency from line 3 (find the product) on line 2 (find the sum).

Concurrency

This also helps explain the difficulties of concurrency. Earlier, I said that the state was a line number and a map from variable name to value. There is actually another argument to the map: time. The problem is that you don’t have a lot of control over time. The only time you can use is “now”. As long as everything follows one flow of time, that really isn’t a problem. But, multiple threads means multiple state machines that each have their own time.

With the shared memory model of concurrency, you access variables from other state machines and have variables that are used by other state machines. These time-steps of these machines are often out of sync. So, you may access a variable by the right name, but at the wrong time. If you could specify the time, that would make it easier. But, you are limited to the current time.

What that leaves is to manipulate time itself. That is what tools like mutexes and semaphores are really doing. They stop time on one machine to sync it with time on another machine. However, this process is undoubtedly difficult. Errors and runtime exception are both easy to make and hard to debug.

The cause of this difficulty lies within the concept of time. The tools for managing data and the tools for managing time are separate. The variable accesses are used for accessing data. Meanwhile, the mutexes and semaphores manage the time. When you have the same ideas in two places, that is simply a chance for something to go wrong.

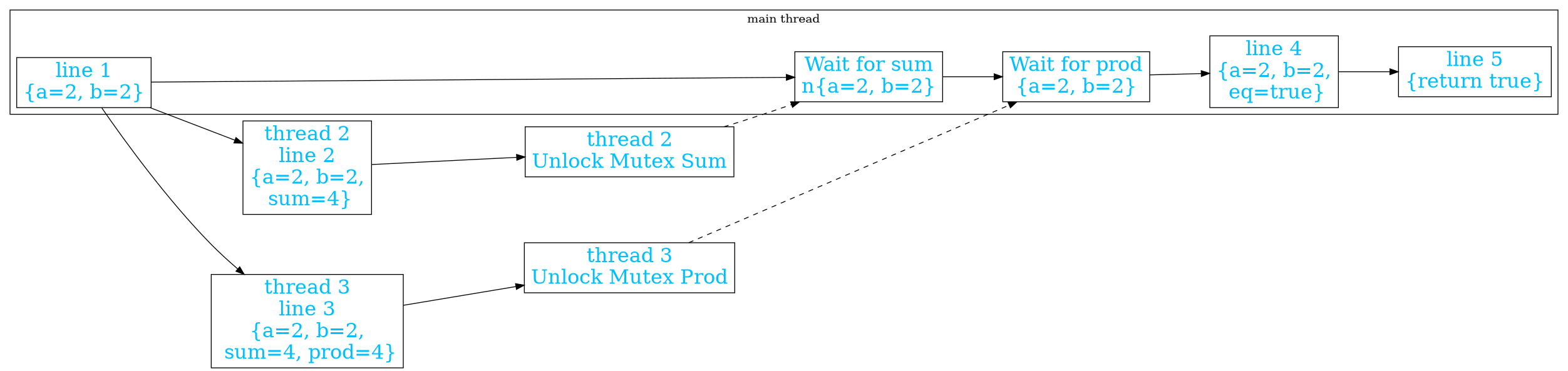

When put into a diagram, you can see all of the extra states and arrows used to manage time. This seems far more complex than the simple imperative system above. However, it is necessary in order to remove the dependency of the product on the sum and allow them to run in parallel. While these trivial operations have little benefit in being run in parallel, it stands as an example of more advanced behaviors.

Message Passing

The natural progression for this train of thought is to unify the control of data and the control of time. The scheme for that is message passing. While the idea is most popular as part of go, other languages have adopted the same system as well.

The idea behind it is to only have your threads communicate by sending messages from one to another. So, one thread will send a message while another thread will await the message. These messages occupy both the concepts of data and time. While sending a message does not affect how your state machine progresses, awaiting a message means you have to wait until the appropriate time on the sender’s state machine. With this, the data and time work in unison.

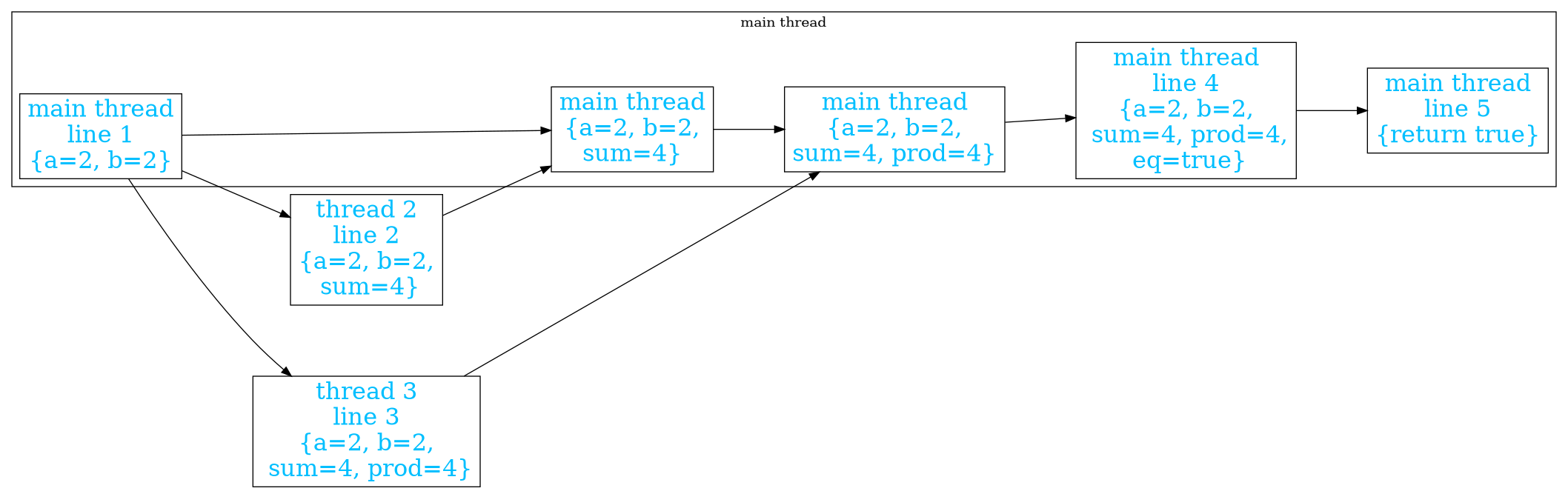

This diagram of what happens in message passing is clearly simpler than the previous one of concurrency. It removes the unlocking states on the other threads to replace with a message. The easily forgotten waiting states are also removed and replaced with states to retrieve the message. Those states are impossible to forget as without them it is impossible to access the sum and product.

Leaving Time

While managing the time better is an improvement, what could we attain by leaving the concept of time altogether? Before that, we need to think about the purpose that time, the state machine’s time-steps, was created for in the first place.

The purpose of time is to manage precedence. A value that you compute in one time step might depend on other values. This dependency is managed through time. You must compute values in an earlier time-step than the time-steps in which you use those values.

The biggest problem with time lies here. As a measure of precedence, it is very imprecise. There are many values that were computed in previous lines of code that may not be required for the current line of code. Figuring out which values are necessary and which ones are not can be tricky. They can be especially tricky when calling functions that hide memory mutations inside them.

In order to replace time, you need to develop a new system of precedence. One such replacement can be found from the world of functional programming. In functional programming, a pure function is one which does not access any global state - it depends only on it’s inputs and has no effects besides returning an output. While pure functions exist even in other languages, functional programming tries to focus on them because they form a full system of precedence.

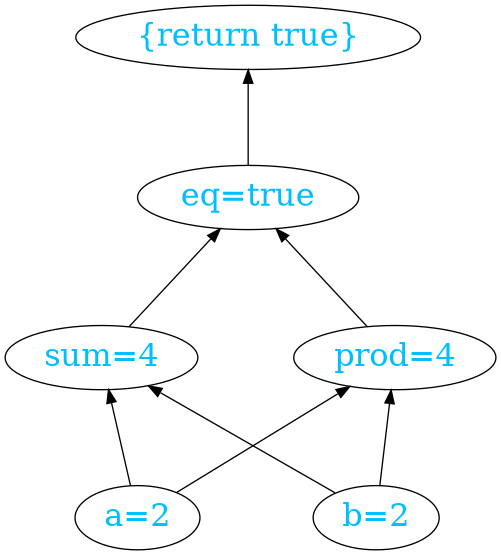

Draw in the diagram below, you can see the same code as it behaves functionally. It is now clear which values are inputs to every computation. States lacking any connection between them can be done in parallel, although deciding if they should be done in parallel is a different question.

With only pure functions, the inputs to a function must be computed in order to compute the function. Nothing besides computing the inputs has any effect. Therefore, the function application itself becomes the system of precedence. Unlike time, it is far more precise. The arguments to a function lack any precedence between them, so they can be computed in parallel. Given only this rule, a functional program can be automatically parallelized.

Imagine combining this functional precedence alongside multi-threading (or an equivalent distributed system). Without time, using shared memory is impossible. However, a message passing approach could be used. In that case, the message passing would form a second form of precedence alongside the function application. However, the benefits of this approach are questionable. It could divide the complexity making the system easier to manage. It could also make it more complicated by introducing new dimensions of complexity. This remains something to explore in the future.

The last piece influence of time comes back to the story of debugging. As I said earlier, debugging allows you to move through time and view the state of the application at various time-steps. One natural consequence of that is that time naturally moves forwards, and debuggers can only allow the program to flow in it’s natural direction as well. There are historical debuggers that try to trace the program and then let you move back and forth through the execution sequence, but they are not that common. Without time, the program becomes essentially a tree. You could explore the tree by moving down into children and up into the parents, a simpler form than debugging to the next step. Now, you can precisely explore the tree to where your program went wrong making it easier to find the problem without requiring many debugging runs.

Conclusion

Time-steps make a relatively straightforward system to reason about. They also match up well with the actual hardware underlying the systems however. However, the idea of time-steps loses out with increasing complexity of programs, managing concurrency, debugging, and clearly defining precedence in programs.

Programming languages don’t have to be bound by the realities of the hardware. Using a language that more honestly describes the problem domain will only make it easier for humans and compilers alike to understand. It is time to move beyond time.

For more interesting programming ideas, check out the programming language I am currently developing: Catln. The documentation has explanations about the language design and the fundamental purposes behind it.

Comments